For any who have ever experienced caving, you will remember unsure footing, tight squeezes and low-hanging rocks and the claustrophobic feeling that can come in the moist earthy air. You will be aware of how extraordinarily dark it can be in the gloomy underground. It can be stifling and unsettling in the depths of a cave, but with light to guide the way, the experience can instead be extremely fulfilling.

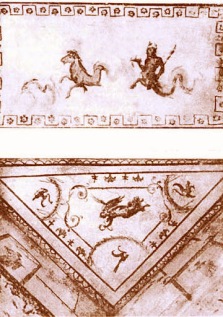

From the Latin word “Grotto”, meaning small cave or hollow, the term grotesque was originally ascribed to Ancient Roman art by Renaissance observers. Bartók explained how the origins of the term came from Renaissance explorers who dug out niches under villas to find the macabre frescoes depicting half-animal, half-man forms. By the 18th Century, the term grotesque had come to be used to describe uneasy or bizarre forms in general, and around this time the literary world had started to use the term to define mixed-genre work, principally comic tragedy.

Something about the cavernous origins of the term grotesque seems to ring truer with the cross-genre idea than just of the half-animal, half-man forms of grotesque art coming to represent the bizarre in popular media. Political satire often takes the most tragic and outrageously upsetting elements of society and morphs them into a comedic pill that is easier to swallow. But by plunging into in-depth political ideas, the comic element can also provide a stark contrast to the tragedy, like a light in a dark recess, often emphasising the tragic element more than a pure-bred tragedy could.

Film has ducked and weaved into grotesque tragicomedy since its early days. Charlie Chaplin’s famous satire of Hitler’s war machine, The Great Dictator, blends the dark undertones of Nazi Germany with slapstick and wit, making the film both entertaining and affecting. The crossing of genres afforded Chaplin the opportunity to use his abilities as a maestro of comedy to both belittle Nazi Germany and also to place comparative emphasis on the more biting realism of the harsh oppression of the Jews inside German borders at the time. As a result the filmmaker’s powerful speech at the climax of the movie seems far more significant in the overall context of unmitigated silliness. The film was controversial, particularly in Nazi Germany, where Chaplin’s lineage was questioned and the star was repeatedly mocked.

With darker humour still, author Salman Rushdie’s descent into religious history in the novel The Satanic Verses was answered with an even harsher political outcry. The book deals with a variety of religious, cultural and political themes, using imagery comparing life in India to life in the west and creating a melting pot of spiritual observations. Mostly, the story is a twisting tale of fantasy and observation, rich in humerous undertones.

It seems from a reading of The Satanic Verses that the intention wasprobably more one of academical witticism than outright blasphemy, but for his trouble Rushdie earned himself a fatwa calling for his death from extremist Islam, issued in 1989 by Supreme Leader of Iran Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. When questioned about the fatwa, Rushdie commonly responds with witty retorts, seemingly unabashed by the controversy surrounding the novel.

German artist Martin Kippenberger was another commentator who disregarded controversy in the name of farce. Kippenberger used the literary grotesque to paint satirical images of modern life, bamboozled by what he viewed as the ridiculous notions of propriety and high society.

Only truly recognised after his death, Kippenberger was a great political spelunker, diving deep into the recesses of bureaucratic inanity and digging up tongue-in-cheek responses to 1980s and 90s western society. With Likeable Communist Woman (1983), Kippenberger strove to “infuriate petit-bourgeois and leftist sympathiser alike” (quote from Tate Modern). The expressive portrait, painted by a German in a period where the Berlin wall seemed destined to stand eternally, played both as an insult to anti-communist propaganda, but also as a subtle jibe at leftist sensibility.

Essentially, Kippenberger’s art is a mockery of the ridiculous notion of sensibility. Another of Kippenberger’s most obnoxiously daring works was the brazen Martin, Into The Corner, You Should Be Ashamed of Yourself. This sculptural self-portrait was made in response to the art critic Wolfgang Max Faust accusing Kippenberger of Neo-Nazi behaviour. Kippenberger dismissed the sensitive nature of social faux-pas and exchanged it for the truly ridiculous. His work remained mockingly derisive throughout his career.

In the deepest recesses of the cave of the grotesque, the ridiculous rules supreme. The darker the political undertones, the more light humour can juxtapose with it, piercing into the vacuous hole of political rockiness and emphasising it. Political satire reinforces that the best way to reveal darkness is to shroud it in light. Political satyrists are the torch-holders, crawling into the grotesque and revealing the beauty in the depths.

Grotesque is the dark niche where great beauty can be found. Grotesque is the blending of contrasting styles to create a powerful sub-genre. Grotesque is, in the literary sense, grotesque!

At the heart of the bizarre, the consequential. At the heart of the grotesque, the grave. At the heart of the ridiculous, the sublime.

All photography is my own and subject to copyright unless stated, please credit any reproductions to this blog or contact (contactmoonunderwater@gmail.com) for more information.

[…] Moon Under Water posted an interesting piece about the grotesque and satire today and this gave me the idea to plug a book called The Grotesque and the Unnatural that came out recently. In fact, I got my copy just earlier this week and it looks very impressive. (c) Cambria Press […]